For several years now, efforts have been taken around the world to control and address the effect of human activity on the planet. To that end, in 2016, more than 190 nations committed, via the Paris Agreement, to improve their objectives and strategies in order to limit global warming to below 1.5°C. This instrument has served as a framework for the development of tools to improve environmental conditions.

Carbon markets play a part in this framework. Their operation is based on one premise: companies and/or governments take actions to reduce, cancel or avoid CO2 emissions from the atmosphere. If these are beyond the obligations acquired, the surplus can be traded as a carbon credit (1-ton CO2 = 1 credit).

There are markets around the world in which these credits are sold, which are differentiated based on the rules under which they operate. There are compliance markets, including those linked to the Kyoto Protocol, which consist of the development of projects promoted by countries with commitments to reduce emissions, and obtain credits. There are markets of prior compliance (e.g., European market), in which maximum limits of polluting gases are set for companies which can trade their surpluses if they achieve greater reductions. And there are Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCMs), in which emission reductions that are not eligible for compliance markets are traded.

VCMs have emerged to complement mandatory compliance markets. Their dynamics are based on emission compensation. That is, if a company emits greenhouse gases (GHG) above a certain threshold, it may seek to offset such excess emissions by purchasing bonds or credits from other projects that have been certified (by an authorized third party) to capture greenhouse emissions.

Advancing voluntary carbon markets

Unlike mandatory compliance markets, VCMs do not have a registry to take stock of projects and their features. At a global level, there are different initiatives to quantify the market size. One of the major initiatives is the Voluntary Registry Offsets Database, developed by the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project at the University of Berkeley (this tool records the projects of the four major certification agencies for voluntary carbon offsets: American Carbon Registry (ACR), Climate Action Reserve (CAR), Gold Standard and Verra (VCS).)

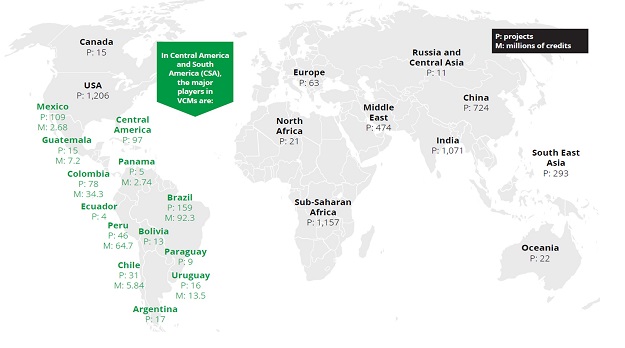

According to the Database, at the regional level (Figure below), nine out of ten projects are concentrated in North America (mainly the United States). Elsewhere, (as our Deloitte studies found, based on public data) Africa stands out because it only accounts for three percent of polluting emissions globally, but has become one of the most relevant regions in the field. It comprises 20 percent of all VCM projects, generating almost 11 percent of all credits registered and identified. In contrast, in countries such as China, which generates 26 percent of emissions, only nine percent of projects have been developed.

Registries indicate that the territorial characteristics of the countries and regions that have issued the largest number of credits are closely related to the feasibility for the development of projects that have not only contributed to securing their natural capital but have also established financial schemes that support their sustainability.

Geographic distribution of VCM projects. Sources: Deloitte with information from Voluntary Registry Offsets Database, Berkeley Carbon Trading Project, University of California, Berkeley.

In Latin America, the first Emissions Trading System was launched in Mexico in 2020, with its pilot program “Emissions Trading System”. The first of its kind in the region, the program covers the energy and industry sector (40 percent of national emissions of polluting gases). In Uruguay, as we explained in detail in our Point of View, Deloitte developed the first carbon offsetting project related to the livestock sector. An improvement of breeding practices and grazing techniques led to a reduction in emissions, which then saw an improvement in the activity itself.

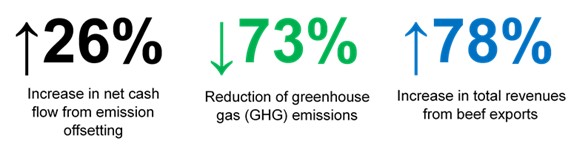

For this project, with a conservative estimate of only 50 percent adoption, the following results were obtained:

Market size

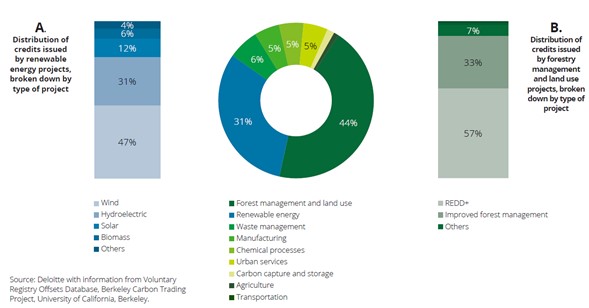

According to the database of the University of Berkeley, as of November 2021, approximately 5,800 voluntary offset projects had been carried out, which avoided, reduced or sequestered around 1.1 billion tons of CO2. Of these, 44 percent relate to forestry management and land use (Figure below). Most of these projects (nearly two out of three) are related to the Reducing Emission from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REED+) framework. This initiative is supported by the United Nations as a mechanism for the conservation and sustainable management of forests, in line with the social and economic dynamics and features of the jurisdiction in which they are developed. It’s based on the creation of financial incentives that help them become sustainable over time, thus contributing to emissions reduction.

As for the projects related to renewable energy generation (33 percent of total registered projects), nearly 80 percent are focused on wind energy and hydroelectric power plants. The remaining projects are mostly focused on the improvement of procedures, substitution of substances for less contaminating ones, recovery of waste, and replacing energy with lower-emission sources.

Markets in constant innovation

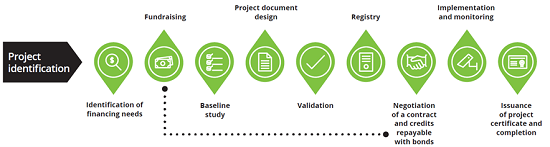

Another benefit of these markets is their ability to implement innovative processes. For example, the project lifecycle (figure below) is involved with the identification of projects to the negotiation of the contract for the issuance of certificates. In the case of voluntary markets, the parameters of existing projects and the standards of certification agencies could allow for a pre-estimation of the project’s potential for credits. Mainly, they could serve to foster fundraising and, thus, meet the technology and training needs inherent in these type of projects. In this situation, financing could be repayable out of the project’s own certificates or credits.

Carbon banks

Another example is the development of carbon banks. The participation of a government agency is key as it promotes greater attractiveness among the owners of the projects by avoiding direct marketing with companies. As they are less exposed to market fluctuations, banks can act as an intermediary between carbon credit holders and potential purchasers who need them to reduce their emission levels. In purchasing the credits, it ensures the best prices through market mechanisms (e.g. auctions) and then earns a trading margin to continue promoting the activity.

Option will be strengthened in the future

There are areas where VCMs could be promoted. However, to exploit their potential, it is also necessary to recognize that projects could affect other economic sectors and face regulatory obstacles as well as technological entry barriers. These can be overcome if good practices are adopted and if sectors operate with innovative solutions (for instance, through the involvement of fintechs).

Over the next years, voluntary carbon credit markets will keep growing, mainly driven by the increasing number of companies looking for strategies to achieve a more reasonable balance of emissions. The structuring and development of projects are vital for this instrument to become a profitable option and to, more importantly, meet the flexibility feature inherent in voluntary offset markets and contribute to reducing emissions.

VCMs have emerged as a complement to mandatory mechanisms. They have gradually transformed to become a more viable and attractive option for companies that have set their emissions targets and, at the same time, become a new form of revenue for different sectors. However, there are still gaps to be filled. Above all, is the need for them to be designed so that projects with potential can be linked with actors or resources for them to be carried out, always recognizing the particularities and regulations of the places in which they are developed.

At Deloitte we are committed to generating tools that contribute to the improvement of environmental conditions. For further information, please refer to the Point of View on VCMs that we developed with an analysis of market trends and how it complements other mechanisms.

Pablo E. Verra has over 20 years of impact investment & advisory experience in Emerging Markets. He’s the lead partner & regional head of public sector, impact and development finance at Deloitte Spanish Latin America. He can be reached at pverra@deloitte.com