Images are powerful things; they shape the way we see the world. My favorite photograph captures a private moment between Martin Luther King Jr and Harry Belafonte: two giants in the civil rights movement with all the gravitas that implies. But this image tells a different story: it shows two friends laughing, and the composition is great. MLK is laughing so hard he’s falling out of frame. I’ve met Mr Belafonte through the prison photography work I do, and we’ve talked about this powerful image and what it means to him.

It’s that power that I wanted to bring to the conversation around criminal justice reform in the United States. It’s finally being talked about, but the conversation is rarely led by those directly affected by the system. It starts with using the wrong language. People who have not been incarcerated use terms such as “ex-con”, “felon”, and “inmate”. These are reductive, inhumane labels that last a lifetime. The men I met told me they prefer the terms “incarcerated” or “formerly incarcerated” because they describe a person’s circumstances and remove the implicit blame and sense of permanence.

This really hammered home for me the point that the most informed voices to speak about a community are those of the community members themselves. These are not my stories. No one else could tell their stories for them. For this reason, I very intentionally made sure the stories were told in their voice, including their diction, their slang, their grammar.

Building trust with these men was important, of course it was. I was asking them to open up, whereas society usually tells men not to share their emotions. I started each conversation by asking about their hero or best friend when they were growing up. Rahson laughed, saying that’s not what he expected me to ask. When I asked what he was expecting, he said “Something about my crime.” Other people might have only been interested in what landed these men in prison, or what prison was like, but I wanted to understand their full story—growing up, inside prison and what life after was like. From the onset, the men knew I was interested in them as a whole person, rather than their biggest mistake.

And I think that helped them trust me with their darkest moments. Honestly, I was surprised by what I learned about men I had known for years through my other work. Take Sean, where a professional relationship turned into a friendship full of mutual respect and inspiration. While interviewing him for this book, I learned things about him I never did before, despite a decade of friendship.

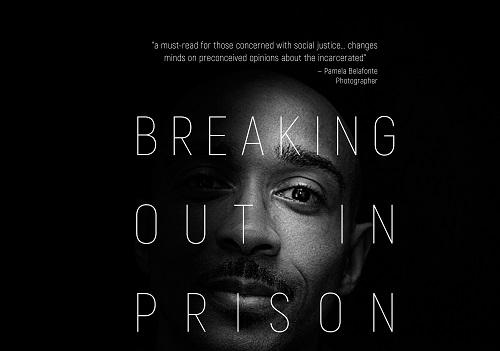

As a humanitarian photographer, I capture stories as they happen in front of me. The story arc of this book goes back decades, making it impossible for me to retroactively capture those moments through the lens of my camera. So I had to visually show the transformation of these men in a different way. Walking home one night, I caught a glimpse of the moon between two tall NYC buildings. I started thinking about the man in the moon and how he’s only visible when the moon is full. It made me realize how we can only know a person after hearing their full story – not just a silver of it.

However: capturing these stories, changing the way we see the issue of criminal justice reform—that’s only the first step. I want people to read this book and start asking about how they can get involved. There are lots of ways, if only we started asking the question. First, support prison rehabilitation programs. Each facility in the country has different programs to create new opportunities for people post incarceration. Find one that resonates with your passions – education, music, animal care, Shakespeare, auto body repair, cosmetic schooling – or look at programs offered at your local facility. Bring your own experience into it and think about what you can personally contribute in terms of skill set or financially support their work.

But also, the most effective way to end mass incarceration is to not send more people to prison. Creating better opportunities for young people who may be funneled into the cradle-to-prison pipeline would stop the flow. Provide a job or offer mentorship for at-risk youth through organizations already working within their communities. You could change these communities for generations to come.

Finally, we need to change the laws. Most laws and policies affecting incarceration occur at the local and state level. Reach out to elected officials about issues that you care about – allowing formerly incarcerated people to vote, banning the box, eliminating cash bail – and ask for their support in changing harmful practices that effectively disenfranchise or criminalize poverty.

Babita Patel is a humanitarian photographer documenting numerous social issues around the world. Her work has appeared on ABC, Al Jazeera, Forbes, The Guardian, HBO, NBC and PBS, and exhibited across the globe, including New York, Los Angeles and Lisbon. Babita is the founder and Executive Director of KIOO Project, an NGO that advances gender equality in economically challenged communities. Her new book Breaking out in Prison can be found on Amazon.

Wonderfully spoken by a humanitarian who focuses on the subtleties in life that tell the real human story.