It started to get grim for Frederick Dick in October 2020. Retired and a grandfather in Inuvik, Northwest Territories, he and his wife provide for several kids and grandkids. Much of his pension goes to rent. And groceries in northern Canada can be three times the amount compared to southern areas.

“It’s not cheap up this way,” Dick says. “We were waiting for public housing, but the condo was taking my whole pension. We didn’t have but a few dollars left for food and we had to access food banks.”

2020 was tough for everyone. But Dick describes a whole new level of adversity. He explains how his grandkids did not have beds or dressers and, on most days, the fridge had little to offer. And then for two months, his power was cut off.

“They don’t care if it’s 40 degrees below, they’ll cut you off,” he says. “We were really struggling.”

It was around this same time that he stumbled across Emily Fudge, founder and executive director of Indigenous Kids Network of Canada (IKNC). “My daughter was checking out this program on the internet,” Dick says. “She told us about this Jordan’s Principle that help struggling families. We got a hold of Emily and she told us what to do.”

IKNC is a non-profit which links First Nations families with a federal funding stream called Jordan’s Principle. Initiated in 2016 and named in memory of Jordan River Anderson of Norway House Cree Nation, Jordan’s Principle assists First Nations children in accessing needed services and supports.

“The application process can be difficult, with many hoops to jump through, so we walk families through it, step-by-step,” Fudge says. “We conduct a needs assessment to establish the child’s needs and then put together the application by helping families collect supporting documentation and obtaining a letter of support from a professional.”

Since her organization began in January 2020, Fudge has secured over half a million dollars in funding for nearly one hundred First Nation children and their families. The funds have been used for professional services including educational assistants, speech therapists, and the purchase of medical equipment. But funding can also be used for more basic items. “We’ve provided families with food, formula, diapers, clothing, and beds,” Fudge says. “Under Jordan’s Principle, we can help families apply for any services and supports in the areas of health, education, and social services. We work to meet the needs of their children that existing services are unable to provide.”

She describes how IKNC was able to secure beds, blankets, and dressers for Frederick Dick’s grandchildren along with several months of rent relief, with water, electricity, and grocery bills covered.

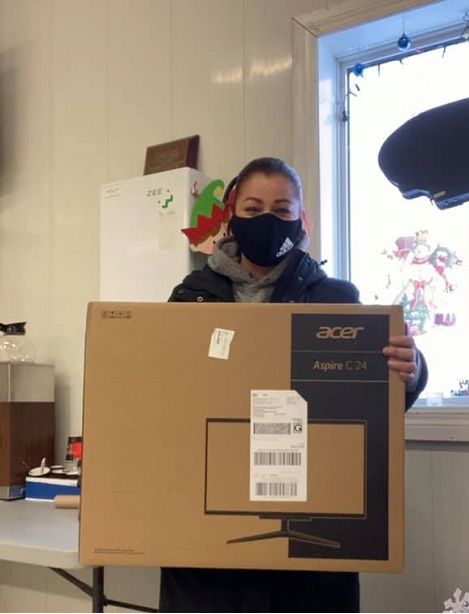

During the pandemic, IKNC also received a grant from the Canadian Red Cross for a COVID-19 relief project. Her organization coordinated the delivery of activity packs to nearly 400 First Nations children to help with educational needs. The packs included flash cards, workbooks, Lego kits, games, and other interactive learning activities.

“Many children live in isolated and remote communities and don’t have access to the same supports and services as other Canadian children,” Fudge explains. “Through Jordan’s Principle, we’re able to close some of those gaps.”

With a team of four volunteers, IKNC supports anywhere between 10 to 20 families each month. And they are hoping to grow those numbers. Fudge says her goal is to design a website to attract donors. She is also keen to advertise Jordan’s Principle broadly and secure funding to hire a coordinator.

At the same time, Fudge realizes providing funds for necessities is welcomed, but it will not solve root issues of disparity and inequities. “The solution is very complex,” she says. “Many Indigenous children are still receiving less. We as Canadian citizens have a responsibility to demand better from our politicians because every child has a right to grow up happy and healthy in our country.” She describes how much of the current challenges in First Nations communities are a result of colonialist policies forced upon Indigenous people which have resulted in inequalities and historical disadvantage.

“When I observed firsthand the inequities and injustices that children in the north were experiencing, I was shocked,” Fudge says. “But I knew I had to be part of the solution. Jordan’s Principle is a step in the right direction. But the Canadian government can definitely do more by adequately funding quality health, education and social services for Indigenous people of all ages.”

Frederick Dick agrees that system changes are needed. But he remains grateful for the sense of relief that comes with immediate financial aid. “It sure helps with all our bills,” he says. “The program is good for the people that really need help.”

Dick has since advertised the services of IKNC to relatives and neighbours in hope to lessen their financial burden as well.

“It’s not only me; she has helped hundreds of people,” Dick says of Fudge. “For us, we’re doing okay. But if it wasn’t for Emily helping us, we wouldn’t have made it.”

Benjamin Rempel is a writer and essayist specializing in public health and social justice. His work has been featured in The Toronto Star, National Observer, Our Canada, The Standard, among other outlets.

I am wondering if the funding through Indian affairs to each indigenous nation is being administered equally amongst families. If not, who monitors these monies supplied through Federal tax dollars to ensure that payments are paid out in a fair process?

If not, why not?

Thank you for any insight you may have.

Hi Eve. I am the founder of IKNC – I have spent some time on reserves in Ontario and have seen the issues that you mentioned and also heard many testimonies from band members about this. I think generally how it works is the money is sent directly to the Chief and Councils and they are responsible and make the decisions on how to use and spend the funds. I’m not sure why the government isn’t doing more to hold them accountable for where the money is going.

I recently just came across this non-profit called The Band Members Alliance and Advocacy Association of Canada – They advocate on behalf of band members that have experienced financial abuse by their chief and councils. This is a quote from their website:

“In some places in Canada, there are native Band Councils that engage in self-serving practices. These kinds of Band Councils also behave in a way that show favouritism and nepotism with housing, employment, health, education and other broader areas of concern. Any Band member that dares speak out risks facing retribution. No government can hold Chiefs and Band Councils in Canada accountable. There is no ombudsperson that oversees or investigates Chiefs and Band Councils in Canada, either.”

Hello just recently I still broke down. . . As the Jordan’s Principle Case Manager I was approved for 1.2 million and my second proposal was approved at 1.6 million. I did not see this money go to what I proposed for mental wellness, land based, Indian residential school & more. In my proposal I included $dollars to hire 10 Educational Assistants and only 3 were hired. A huge lump sum I know went to a Child & Family Services Supervisor during covid for the community. In my proposal I wanted cultural workers and land based workers hired. I wrote out the advertised job opportunities. 3 people applied and they were not interviewed. The money was spent elsewhere because I was not approved to help families. I mentioned this to Joe Gacheru and he told me that it was a band issue. We never got our Jordans Principle building not did we have a sensory room anywhere. Most of the time the health director & building healthy communities worker wanted to play big bingos with expensive prizes like bedrooms suites etc. The woman who won the bedroom suite never recieved it. When I asked about the bedroom suite they told me they lost it. I was fired on February 13th. 2020. This not right. This is sad. I can say more. Please contact me if you think this is serious. To me it is serious. The chief and council should not be given the funds to handle. Even the health director should be questioned because monies are spent on bingos and games. They have fishing Derby’s for expensive prizes and huge money prizes. Money prizes for Halloween Decorating contests, Christmas, Easter etc.